Theodore Roethke created intimate, introspective poems distinguished by lyricism and a sensual use of imagery. Best known for his poems about the natural world, Roethke was profoundly influenced by the events of his childhood and mined his past for the themes and subjects of his writing. He mastered a variety of poetic styles, from formal rhymes to experimental free verse, and received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1954 for his collection The Waking (1953).

Theodore Roethke created intimate, introspective poems distinguished by lyricism and a sensual use of imagery. Best known for his poems about the natural world, Roethke was profoundly influenced by the events of his childhood and mined his past for the themes and subjects of his writing. He mastered a variety of poetic styles, from formal rhymes to experimental free verse, and received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1954 for his collection The Waking (1953).

Roethke was born on May 25, 1908, in Saginaw, Michigan, where he spent time as a child exploring the large greenhouse owned by his father and uncle. In 1929, he received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan, and he took graduate courses there and at Harvard University before embarking on a teaching career at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania in 1931. During this period, his poems began to appear in the New Republic, Saturday Review, and other publications. He received a master’s degree from the University of Michigan in 1936.

The tight, carefully constructed poems of Roethke’s first collection, Open House (1941), included short metaphysical works about nature and the self. Written in conventional poetic forms, they include “The Light Comes Brighter,” in which Roethke describes the coming of spring, when “buckled ice begins to shift” and “the cold roots stir below.” In the title poem he writes more personally: “My truths are all foreknown, / This anguish self-revealed, / I’m naked to the bone, / With nakedness my shield.”

Roethke found his greatest and most joyful inspiration in the landscape of his childhood. Published in 1948, his second collection, The Lost Son and Other Poems, included the landmark “greenhouse poems.” Written in a looser, more experimental form than his earlier work, the series drew on Roethke’s recollections of the plants and insects, smells, and organic sensations of the family-owned greenhouse in Michigan where he spent his youth. “I can hear underground, that sucking and sobbing,” he writes in “Cuttings (later),” “In my veins, in my bones I feel it . . .” The poems range from tender meditations on orchids and carnations to rich descriptions of even the most mundane activities, such as pulling weeds and transferring plants from one location to another.

His relationship with his father, who died when Roethke was 15, also loomed large in the poet’s imagination. “He does not put on airs / Who lived above a potting shed for years,” he recalls in “Otto.” “I think of him, and I think of his men, / As close to him as any kith or kin.” Similar recollections surface in “The Premonition” and “My Papa’s Waltz.”

Throughout his career, Roethke changed styles frequently, moving dramatically from terse, formal rhymes to highly original free verse—and back again. For his third collection, Praise to the End! (1951), he re-imagined the world through the eyes and voice of a child. In the lengthy title poem, he adopted the comforting rhythm and nonsense sounds of a nursery rhyme: “Mips and ma the mooly moo, / The likes of him is biting who, / A cow’s a care and who’s a coo?— / What footie does is final.”

A passionate teacher praised for moving and exciting his students, Roethke taught poetry at colleges and universities across the U.S., including Pennsylvania State College, Bennington College, and the University of Washington. He also suffered from bouts of mental illness and a recurring feeling of discomfort in his own skin, but he was unafraid to confront his innermost thoughts and emotions in his work. “What’s madness but nobility of soul / At odds with circumstance?” he asks in “In A Dark Time.” “My soul, like some heat-maddened summer fly, / Keeps buzzing at the sill. Which I is I?” In 1953, he married Beatrice O’Connell, formerly a student at Bennington College.

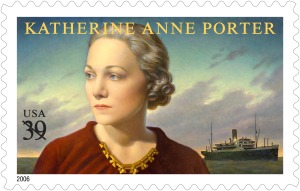

First Day Covers (click to order)

In addition to the Pulitzer Prize, Roethke’s many honors include the Bollingen Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, and a Fulbright lectureship. He received the National Book Award in 1959 for Words for the Wind: The Collected Verse (1958). “I Am!” Says the Lamb, a book of poems for children, was published in 1961.

Roethke died on August 1, 1963, on Bainbridge Island, Washington. Published posthumously,The Far Field (1964), a collection of poems, including love poems, received the National Book Award in 1965.

Theodore Roethke is one of ten poets featured on the Twentieth-Century Poets pane. The stamps will be issued on April 21 in Los Angeles, California, but you can preorder them today!