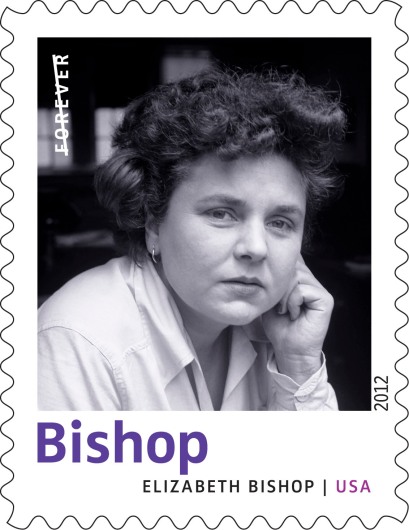

Elizabeth Bishop has been called a “writer’s writer’s writer,” suggesting the admiration other poets feel for her work. Her total output was small, but she polished her poems to gleaming perfection. In works such as “Filling Station,” “The Moose,” and “First Death in Nova Scotia,” she displayed the precise observation, intellectual strength, and understated humor that continue to win admirers.

Bishop was born February 8, 1911, in Worcester, Massachusetts. Her father died when she was an infant, and her mother, who eventually took her to live with maternal grandparents in Nova Scotia, suffered a series of breakdowns before being permanently hospitalized.

Bishop was born February 8, 1911, in Worcester, Massachusetts. Her father died when she was an infant, and her mother, who eventually took her to live with maternal grandparents in Nova Scotia, suffered a series of breakdowns before being permanently hospitalized.

Despite these disturbances, childhood offered her satisfaction and interest. She loved learning the alphabet. Years afterward, she remembered: “It was wonderful to see that the letters each had different expressions, and that the same letter had different expressions at different times. Sometimes the two capitals of my name looked miserable, slumped down and sulky, but at others they turned fat and cheerful, almost with roses in their cheeks.”

In 1917, Bishop’s paternal grandparents brought her back to Worcester, a wrenching experience. “I felt as if I were being kidnapped, even if I wasn’t,” she later wrote. She lived with relatives, in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, over the next several years, and entered Vassar College in 1930. A librarian there introduced her to the poet Marianne Moore, who encouraged her interest in writing and selected some of her work for publication in an anthology, giving an early boost to her career.

After graduating from Vassar in 1934, Bishop began an extended period of restless travel, staying in New York, Key West, and other places before settling in Brazil, where she lived for the greater part of two decades. She returned to the United States in the late 1960s, finally moving to Boston, where she taught at Harvard University.

In Bishop’s work, opposites are fused. Reticence and control—passionate feeling and also coolness—mark her writing. Her poems walk the line between public and private, the marvelous and the ordinary, and other contradictions. This heightened awareness or “double vision” came to her in childhood, as recounted in her well-known poem “In the Waiting Room,” in which she remembers sitting in a dentist’s office as a girl of six: “But I felt: you are an I, / you are an Elizabeth, / you are one of them.”

Bishop is celebrated for her powers of description and precise observation. There is something of the careful mapmaker’s exactness in her poems, reflected in the titles of several of her books, such as North & South (1946), Questions of Travel (1965), and Geography III (1976). Her poetry is aware of economic inequality and the edgy relationship between rich and poor. “Pink Dog” touches on the brutality of society in regard to outcasts. Scenes of hungry people during the Depression inspired her to write “A Miracle for Breakfast.”

Her autobiographical prose poem “In the Village,” widely considered a classic, presents life in the maritime village of her childhood as enchanting if not fully understood. Poignantly portraying the tension of living with an unbalanced person (her mother), it begins: “A scream, the echo of a scream, hangs over that Nova Scotian village. No one hears it; it hangs there forever….”

Digital Color Postmarks (click to order)

In the words of one critic, her poems “accommodate the smallest details and the largest issues.” Bishop’s poems seem open to almost any subject, including even a dirty filling station, and consistently defy expectation. “First Death in Nova Scotia” finds surprising humor in a child’s struggle to make sense of the death of a younger cousin. In “The Armadillo,” a festive fire balloon splatters against a cliff “like an egg of fire” and sends animals in the vicinity into a panic; with great subtlety, Bishop calls aerial bombing to mind, and “The Armadillo” turns out to be an anti-war classic, comparing human beings to the frightened animal with “a weak mailed fist / clenched ignorant against the sky.”

Elizabeth Bishop died suddenly of a cerebral aneurysm at her home in Boston on October 6, 1979. She received many awards and honors during her lifetime, and interest in her work continues to grow.

Bishop is one of ten poets featured on the Twentieth-Century Poets pane. The stamps will be issued on April 21 in Los Angeles, California, but you can preorder them today!