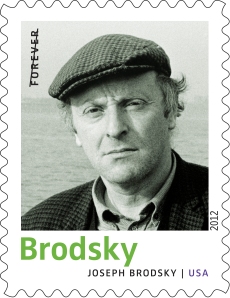

Joseph Brodsky, an exile from the Soviet Union, was the first foreign-born poet to be appointed Poet Laureate of the U.S. (1991–92). His meditative, lyrical elegies, often fused with classical themes, explored personal issues of loss and loneliness as well as such universal ideas as death and the meaning of life. Praised for writing in both Russian and English, Brodsky published several poetry collections in his lifetime as well as three collections of essays. In 1987, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature for “all-embracing authorship, imbued with clarity of thought and poetic intensity.”

Brodsky was born on May 24, 1940, in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Russia. After leaving school at age 15, he worked at a variety of jobs, primarily as an unskilled laborer. He also read voraciously and eventually taught himself Polish and English through poetry. By 1960, his own poems were circulating widely in the underground press.

Brodsky was born on May 24, 1940, in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Russia. After leaving school at age 15, he worked at a variety of jobs, primarily as an unskilled laborer. He also read voraciously and eventually taught himself Polish and English through poetry. By 1960, his own poems were circulating widely in the underground press.

Although Brodsky was not a dissident, he attracted the attention of Soviet officials. In 1964, he was arrested and formally charged with “social parasitism” because of his sporadic employment. Sentenced to five years labor on a farm in the north, Brodsky was released in 1965 after serving 18 months. He continued to write poetry after his return to Leningrad, but despite his growing reputation as a gifted and committed poet, he was ultimately forced to leave the Soviet Union in 1972.

In the years between his arrest and exile, Brodsky wrote one of the most important poems of his early career. Comprising 14 cantos and nearly 1,400 lines, the epic “Gorbunov and Gorchakov” records the dialogue between two patients in a psychiatric hospital, interspersed with the patients’ philosophical monologues and interrogations from their doctors. “I feel my very self’s at stake / when I don’t have an interlocutor,” muses Gorchakov, alone one night. “It is in words alone that I partake / of life.” Writing the poem proved therapeutic for Brodsky, who had stayed in a similar institution for a short period during his 1964 trial.

Brodsky settled in the U.S. in 1972 and had become a U.S. citizen by the end of the decade. He had a self-proclaimed “love affair with the English language” and translated many of his poems himself. He wrote numerous essays in English, and in the late 1980s, he even began composing poems in English. Yet the pull of his homeland—and native tongue—remained strong. As he states in “A Part of Speech”: “What gets left of a man amounts / to a part. To his spoken part. To a part of speech.”

A thread of displacement, loneliness, and loss runs through many of Brodsky’s poems. “I don’t know where I am or what this place / can be,” he writes in “Odysseus to Telemachus,” which draws on Homer’s Odyssey. “To a wanderer the faces of all islands / resemble one another.” In “Lullaby of Cape Cod,” he writes of moving between empires and navigating unfamiliar landscapes, while in “Lithuanian Nocturne” he asks, “Muse, may I set / out homeward?”

Ceremony Program (click to order)

Brodsky never did return to Russia, but he embraced the country he came to call home—and the U.S. embraced him in return. In addition to teaching at universities in Michigan, New York, and Massachusetts, he published poems and essays in the New York Times, Vogue, and other places. He received a grant from the MacArthur Foundation in 1981 and the 1986 National Book Critics Circle Award for Less Than One, a collection of essays about Russian and American poetry.

As Poet Laureate of the U.S., Brodsky sought to make poetry more accessible to Americans. “This assumption that the blue-collar crowd is not supposed to read it,” he stated soon after his appointment, “or a farmer in his overalls is not to read poetry, seems to be dangerous, if not tragic.”

Stricken with a heart condition that made him frail at a young age, Brodsky had a heightened sense of his own mortality, and images of time and death persist in his poems. “Lately I often sleep / during the daytime,” he writes in “Nature Morte.” “My / death, it would seem, is now / trying and testing me.” Brodsky died in New York City on January 28, 1996.

Joseph Brodsky is one of ten poets featured on the Twentieth-Century Poets pane. The stamps will be issued on April 21 in Los Angeles, California, but you can preorder them today!