E. E. Cummings expertly manipulated the rules of grammar, punctuation, rhyme, and meter to create poems that resembled modernist paintings more than traditional verse. His works about love and relationships, nature, and the importance of the individual transformed notions of what a poem can do and delighted readers of all ages. Criticized by some readers for his unconventional and highly experimental style, Cummings eventually became one of the most enduringly popular poets of the 20th century.

Cummings was born on October 14, 1894, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Encouraged by his mother, he wrote poems, stories, and essays throughout his childhood. Eight Harvard Poets, a collection published in 1917,included eight poems written by Cummings while he was a student at Harvard University. His first book, The Enormous Room (1922), was a memoir in the form of a novel. Now considered a classic, this work describes his four-month internment in a French prison during World War I on unfounded suspicions of treason.

Cummings was born on October 14, 1894, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Encouraged by his mother, he wrote poems, stories, and essays throughout his childhood. Eight Harvard Poets, a collection published in 1917,included eight poems written by Cummings while he was a student at Harvard University. His first book, The Enormous Room (1922), was a memoir in the form of a novel. Now considered a classic, this work describes his four-month internment in a French prison during World War I on unfounded suspicions of treason.

Published in 1923, Cummings’s first collection of poetry, Tulips and Chimneys, comprised 66 poems, including what may be his most famous, “in Just-.” Drawing on images from Cummings’s own idyllic childhood, the poem imagines children at play in springtime, “when the word is puddle-wonderful” and “bettyandisbel come dancing // from hop-scotch and jump-rope” at the whistle of the “old balloonman.” Critics praised the collection for its fresh, vivid energy, but the poet’s unconventional style puzzled some of them.

Not satisfied merely to describe a moment or sentiment, Cummings aimed to reproduce experiences directly on the page. He deleted or added spaces between words and lines in order to guide the tempo of a poem. He frequently combined words or created unexpected new ones and used capitalization for emphasis. Punctuation added complexity and nuance. Appearing in Cummings’s 1931 collection W (1931), “n(o)w” mimics the rumble, electrical hiss, and sudden crash of a thunderstorm, when the sky “iS Slapped:with;liGhtninG / !.” A whimsical piece about a grasshopper from No Thanks (1935), “r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r,” has letters playfully jumping in and out of order, obscuring and enhancing the poem’s meaning at the same time.

Cummings loved to paint, and his experience as a painter led him to create paintings with words, poems that cannot be truly understood until seen laid out on the page. For the simple four-word poem “l(a,” for example, he embedded the parenthetical phrase “a leaf falls” within the single word “loneliness.” The poem’s thin, vertical arrangement on the page evokes the graceful cadence of a leaf falling from a tree, while its sparse language communicates ideas of fragility and death, universality and rebirth.

Despite Cummings’s affinity for avant-garde styles, much of his work is traditional. Many of his poems are sonnets, and he even adopted the well-worn pattern of nursery rhymes, particularly in 1 X 1 (1944), a collection that received the Shelley Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America.

Twentieth-Century Poets Notecard Set (click to order)

Nevertheless, Cummings strongly resisted conformity, a theme that threads its way through much of his poetry. “So far as I am concerned,” he once wrote, “poetry and every other art was, is, and forever will be strictly and distinctly a question of individuality.” For “anyone lived in a pretty how town,” Cummings created the quintessential individual, “anyone,” who is loved by “noone.” Disliked by the judgmental “someones” and “everyones” around them, anyone and noone embrace life, content with what they have: “when by now and tree by leaf / she laughed his joy she cried his grief / bird by snow and stir by still / anyone’s any was all to her.”

During the 1950s, Cummings read his poetry publicly in museums, theaters, and educational institutions. He loved performing, and the effort not only increased his audience but also introduced poetry to new legions of fans.

In addition to several award-winning poetry collections, Cummings also published plays, fairy tales, and nonfiction. In late 1950, he received the Fellowship of the Academy of American Poets, one of the nation’s most prestigious poetry awards, and in 1958 he received the Bollingen Prize in Poetry from Yale University.

Cummings died on September 3, 1962, in North Conway, New Hampshire.

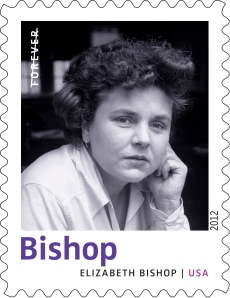

E. E. Cummings is one of ten poets featured on the Twentieth-Century Poets pane. The stamps will be issued on April 21 in Los Angeles, California, but you can preorder them today!

“E. E. Cummings”, 1935

Photograph by Edward Weston

Collection Center for Creative Photography

Arizona Board of Regents

NorthJersey.com shared a video of a special dedication of the Larry Doby stamp at the Patterson, New Jersey, Post Office, while Yankees On Demand posted a video of the dedication of the Joe DiMaggio stamp. DiMaggio and Doby are two of the four athletes featured on the Major League Baseball All-Stars stamps sheet.

NorthJersey.com shared a video of a special dedication of the Larry Doby stamp at the Patterson, New Jersey, Post Office, while Yankees On Demand posted a video of the dedication of the Joe DiMaggio stamp. DiMaggio and Doby are two of the four athletes featured on the Major League Baseball All-Stars stamps sheet.