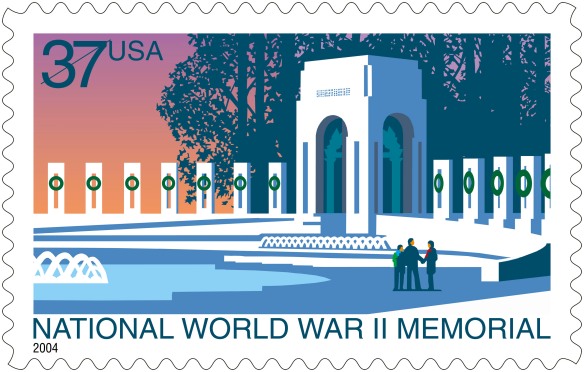

Dedicated on May 29, 2004, the National World War II Memorial is located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument, just east of the Reflecting Pool.

The memorial honors the 16 million Americans who served in the armed forces during the war, and the millions more who supported them on the home front.

On May 25, 1993, President Clinton signed Public Law 103-32 authorizing the American Battle Monuments Commission to build the memorial in or around Washington, D.C. The memorial is funded primarily by private contributions. Construction of the memorial began in September 2001 and it opened to the public on April 29, 2004.

The Second World War is the sole 20th-century event commemorated on the central axis of the National Mall, where it joins other beacons of freedom. The U.S. Capitol and the Washington Monument are symbols of the nation’s founding in the 18th century; and the Lincoln Memorial and statue of Ulysses S. Grant honor the nation’s preservation in the 19th century.

The memorial’s design, by Friedrich St. Florian—an architect based in Providence, Rhode Island—was one of 404 entries received in an open design competition in 1996. St. Florian’s design is intended to create a powerful sense of place that is distinct, memorable, evocative, and serene. Its principal features are the Rainbow Pool and memorial plaza. Ceremonial steps and ramps lead into the plaza, and two 43-foot arches serve as markers and entries on the north and south ends of the plaza. Each state and territory from the World War II era, and the District of Columbia, are represented by one of 56 pillars adorned with bronze wreaths, celebrating the unity of the nation during the war.

Issued on the day of the memorial’s dedication, the postage stamp honoring the achievement and ideals of the Americans who served during WWII was created before the memorial was completed. “The memorial was barely a scratch in the dirt when I was given the assignment,” stamp artist Tom Engeman said. His computer-generated design was based on photographs he and art director Howard E. Paine took of a scale model of the memorial housed in a trailer on the construction site. The stamp art depicts one of the two large memorial arches with a curving row of pillars, set against a dramatic sunset.

What does the National World War II Memorial mean to you?