Katherine Dunham (1909-2006) was the first choreographer to develop a formal technique based on movements from authentic Caribbean rituals, such as an arched torso and undulating spine, hip thrusts and pops, and shoulders that twitch and shrug. “The techniques that I knew and saw and experienced were not saying the things that I wanted to say,” she explained. “To capture the meaning in the culture and life of the people, I felt that I had to take something directly from the people and develop that.”

Katherine Dunham (1909-2006) was the first choreographer to develop a formal technique based on movements from authentic Caribbean rituals, such as an arched torso and undulating spine, hip thrusts and pops, and shoulders that twitch and shrug. “The techniques that I knew and saw and experienced were not saying the things that I wanted to say,” she explained. “To capture the meaning in the culture and life of the people, I felt that I had to take something directly from the people and develop that.”

Dunham technique, as her method came to be called, combined Caribbean and African dance elements with aspects of ballet. It stressed strong core muscles, a flexible torso, relaxed back, powerful knees, and the ability to move parts of the body in isolation. “My real effort,” she recalled, “was to free the body from restriction.”

Her first full-length show, L’Ag’Ya, was set in Martinique and inspired by a folktale about a man who uses a zombie charm to win the love of a woman and exact revenge on his rival. Culminating in the fighting dance of Martinique, L’Ag’Ya debuted in Chicago in 1938 and became one of Dunham’s most popular performance pieces.

This video has no sound, but Dunham’s dancing really speaks for itself!

Later shows drew on the folk and ethnic traditions of the Caribbean as well as Central and South America and Africa. Debuting in New York City in 1940, Tropics and Le Jazz Hot traced the rich legacy of African dance in the Americas and featured Dunham’s popular performance as “Woman with a Cigar.” She also appeared in the successful 1940 Broadway musical Cabin in the Sky, which she helped choreograph with George Balanchine. Bal Nègre, which opened in 1946, included another audience favorite, “Shango.”

Dunham and her dancers received accolades in the U.S. and around the world, but they also encountered racial prejudice. Not only did some hotels and restaurants refuse to serve them, but Dunham and her troupe had to work against the widespread belief that African Americans were incapable of mastering formal dance techniques.

Despite the obstacles, Dunham eventually realized her dream that African-American dance be taken seriously as an art. Audiences worldwide flocked to her shows, and Dunham technique influenced a generation of African-American dancers and choreographers, including Alvin Ailey. Dunham choreographed dance sequences for Stormy Weather (1943) and other films. She also opened a performing arts school in New York City. In 1963, she choreographed a new production of Verdi’s opera Aida for the Metropolitan Opera.

In addition to multiple honorary degrees and other awards, Dunham received the 1983 Kennedy Center Honors for lifetime achievement in the arts, as well as the 1989 National Medal of the Arts “for her pioneering explorations of Caribbean and African dance, which have enriched and transformed the art of dance in America.”

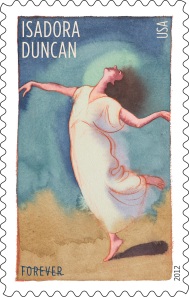

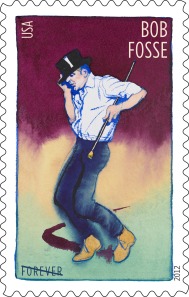

Later this year, Dunham will be one of four choreographers honored on the Innovative Choreographers stamp pane. The others are Isadora Duncan, José Limón, and Bob Fosse. I can’t wait.

Oscars, including one for Fosse as best director, in 1973. That same year, he won two Tony awards as best director and best choreographer for the musical Pippin, as well as three Emmy awards for his direction, choreography, and production of the television special Liza With a Z. No other director has won the “Triple Crown” (Oscar, Tony, and Emmy awards) in the same year.

Oscars, including one for Fosse as best director, in 1973. That same year, he won two Tony awards as best director and best choreographer for the musical Pippin, as well as three Emmy awards for his direction, choreography, and production of the television special Liza With a Z. No other director has won the “Triple Crown” (Oscar, Tony, and Emmy awards) in the same year.