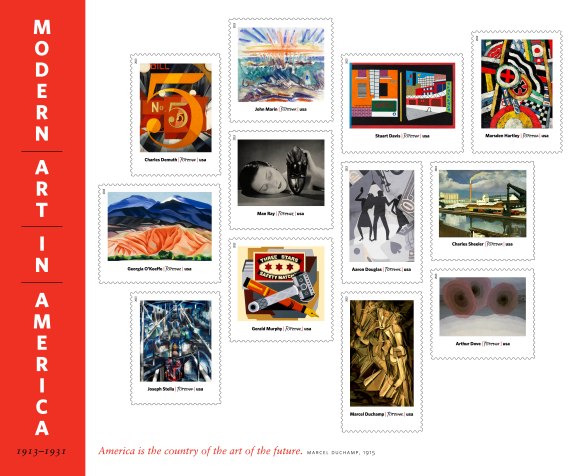

Today we wish a happy birthday to Gerald Murphy, one of 12 artists featured on the Modern Art in America stamp sheet. In less than a decade as a practicing artist, Murphy produced only a small number of works—slightly more than a dozen, about half of them now lost. His career began and ended in the “roaring twenties,” when he and his wife, Sara, were American expatriates living in France. Despite his limited output, he is now recognized as a significant painter whose work prefigured the Pop art of the 1960s.

Gerald Murphy was born into a wealthy family on March 26, 1888, in Boston, Massachusetts, where his father ran a leather goods company. The elder Murphy moved the business, the Mark Cross Company, and his family to New York City in 1892. After graduating from Yale in 1912, Gerald joined the family firm, as expected, but six years later he left for an extended period. In 1921, he and his wife went to France, where they joined a brilliant circle including the writers Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, composer Igor Stravinsky, and artists Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger. Murphy and his wife partly inspired the characters Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender Is the Night, a novel by their friend F. Scott Fitzgerald, who dedicated it to them.

John Dos Passos, composer Igor Stravinsky, and artists Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger. Murphy and his wife partly inspired the characters Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender Is the Night, a novel by their friend F. Scott Fitzgerald, who dedicated it to them.

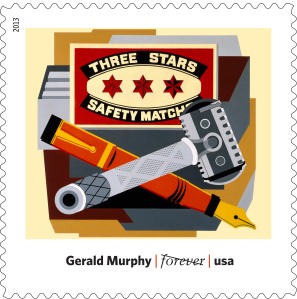

In France, Murphy studied painting with Natalia Goncharova, a Russian artist. His first surviving picture, Razor (shown in the stamp art), from 1924, presents a razor and fountain pen crossed in front of a box of matches, with the objects seen from multiple angles showing the clear influence of Cubism. It is typical of Murphy’s work in its flat, stylized depiction of commonplace objects, presented at a large scale.

Other works by Murphy include Watch, a close-up look at the interior of a pocket watch; Bibliothèque, showing items in his father’s library, including books, a globe, a magnifying glass, and a bust of Ralph Waldo Emerson; and Cocktail, a Cubist rendering of the objects—a cocktail shaker, corkscrew, a martini glass, and so on—associated with making cocktails. Wasp and Pear showed a menacingly large insect feeding on a piece of fruit.

Each envelope in this set of First Day Covers carries a different, affixed Modern Art in America stamp and an official First Day of Issue color postmark. Click the image for details.

As the Jazz Age came to its end with the onset of the Great Depression and as a result of personal circumstances, Murphy quit painting and returned to America, where he concentrated on the family business. He lived in relative anonymity until a brief discussion of his work appeared in a book published in 1956, Modern Art USA, by Rudi Blesh. Murphy was then approached by Douglas MacAgy, the director of the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts, asking if any of his paintings were available for an exhibit that would be dedicated to overlooked American artists. (“I’ve been discovered,” Murphy announced at the luncheon table. “What does one wear?”) That show, featuring five of his works, opened in 1960 and was the first public exhibition of Murphy’s paintings in America. It sparked renewed interest in his work.

In 1962, the New Yorker writer Calvin Tomkins, published a profile of Murphy—later published in book form—entitled “Living Well Is the Best Revenge.” Writer Archibald MacLeish—another friend of Murphy’s—donated Wasp and Pear to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1964, shortly before Murphy’s death that year on October 17. This painting would hang in the museum along with work by some of the artist’s old friends, such as Picasso and Léger.

Ten years later, an exhibit devoted to Murphy’s career opened at MoMA. The show garnered critical praise and solidified Murphy’s growing reputation as a major talent.

The Modern Art in America Forever® stamps were issued March 7 in New York City and are and in Post Offices across the country.