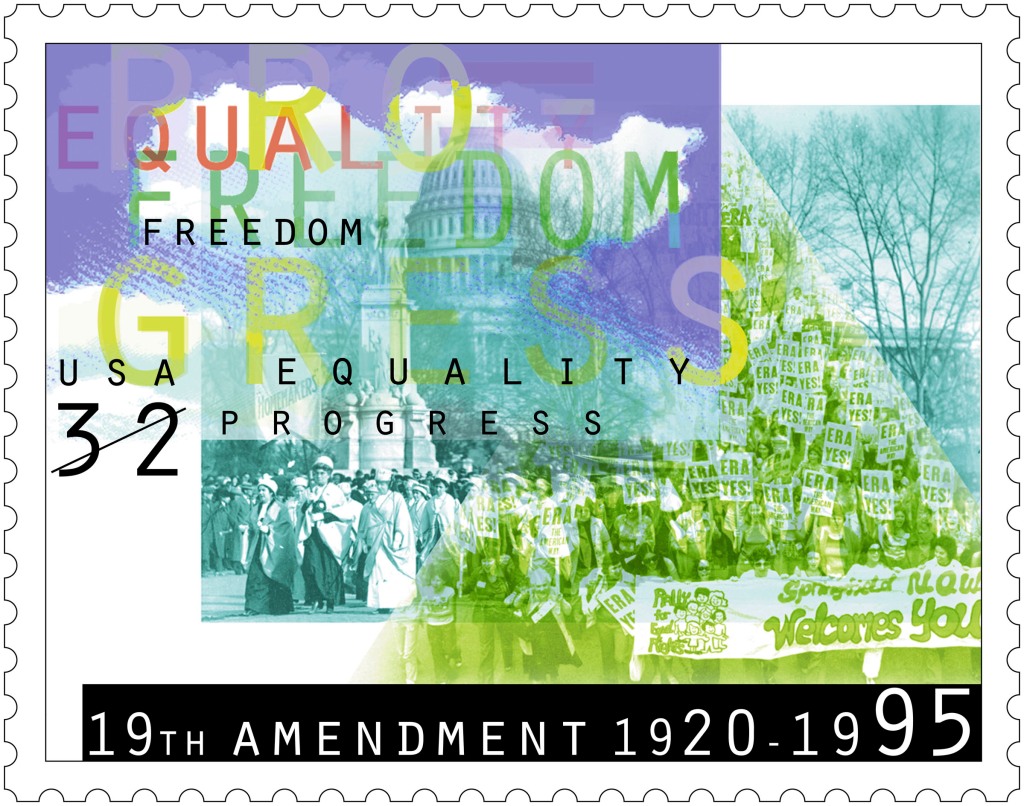

With the passage of the 19th Amendment on August 26, 1920, American women were, for the first time in the nation’s history, allowed to vote—a right which was a long time coming. The seeds of the 19th Amendment were planted in July 1848 at a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. On the morning of July 19, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott unveiled a Declaration of Sentiments and 11 Resolutions, proposing that “woman is man’s equal,” and that she should “secure to [herself her] sacred right to elective franchise.”

York. On the morning of July 19, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott unveiled a Declaration of Sentiments and 11 Resolutions, proposing that “woman is man’s equal,” and that she should “secure to [herself her] sacred right to elective franchise.”

The movement unleashed in Seneca Falls received a giant push when Stanton met Susan B. Anthony at an anti-slavery gathering in 1851. A Quaker abolitionist and temperance worker, Anthony became a willing and able adherent to the suffragist cause. “As I passed from town to town,” Anthony remembered, “I was made to feel the great evil of women’s utter dependence on man . . . Woman must have a purse of her own, and how can this be, so long as the law denies the wife that right?”

Anthony, whose death in 1906 prevented her from witnessing the success of her work, inspired troops with her final public utterance: “Failure is impossible.” The suffragists lobbied on, receiving a needed boost during World War I, when the value of women in the war effort was well recognized. The 19th Amendment was introduced on January 20, 1918, by Jeanette Rankin, the first woman to be elected to Congress. By the war’s end it had cleared both houses of Congress and was sent to the states for ratification. It took less than a year to gather the 36 necessary states for ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Anthony, whose death in 1906 prevented her from witnessing the success of her work, inspired troops with her final public utterance: “Failure is impossible.” The suffragists lobbied on, receiving a needed boost during World War I, when the value of women in the war effort was well recognized. The 19th Amendment was introduced on January 20, 1918, by Jeanette Rankin, the first woman to be elected to Congress. By the war’s end it had cleared both houses of Congress and was sent to the states for ratification. It took less than a year to gather the 36 necessary states for ratification of the 19th Amendment.