Fifty years ago today, some 250,000 people took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The highlight of the event was the powerful “I Have a Dream” speech that Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Fifty years ago today, some 250,000 people took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The highlight of the event was the powerful “I Have a Dream” speech that Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

The march was the brainchild of labor leader A. Philip Randolph, a seventy-four-year-old veteran of battles against racial discrimination. Randolph had proposed a similar march in 1941, but cancelled it after President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed to remove barriers to employing blacks in the defense industry during World War II. Two decades later, with black unemployment double the rate for whites, he again called for a mass demonstration “for Negro job rights.”

Randolph picked up support for his idea in the spring of 1963, after law officer Eugene “Bull” Connor turned police dogs and fire hoses on peaceful demonstrators (many of them children) in Birmingham, Alabama. The protests were part of a campaign led by Martin Luther King, Jr., of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to strike down Birmingham’s segregation ordinances and open up job opportunities for the city’s black residents. King was arrested during the campaign, and wrote his famous “Letter From Birmingham City Jail” advocating civil disobedience against unjust laws. The events in Birmingham sparked hundreds of demonstrations across the nation and drew worldwide attention.

Randolph picked up support for his idea in the spring of 1963, after law officer Eugene “Bull” Connor turned police dogs and fire hoses on peaceful demonstrators (many of them children) in Birmingham, Alabama. The protests were part of a campaign led by Martin Luther King, Jr., of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to strike down Birmingham’s segregation ordinances and open up job opportunities for the city’s black residents. King was arrested during the campaign, and wrote his famous “Letter From Birmingham City Jail” advocating civil disobedience against unjust laws. The events in Birmingham sparked hundreds of demonstrations across the nation and drew worldwide attention.

Hoping to keep up the pressure for change, King and leaders of the major civil rights organizations—the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Conference of Racial Equality, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the National Urban League—joined Randolph in calling for a march on Washington. “We are on the threshold of a significant breakthrough,” King told confidants, “and the greatest weapon is mass demonstration.”

In June, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference announced plans for a “massive, militant, and monumental” demonstration in Washington and across the nation. That same month President John F. Kennedy sent a civil rights bill to Congress. Concerned that a mass demonstration in Washington might actually harden Congressional opposition to his civil rights bill, Kennedy invited civil rights leaders to a meeting at the White House to persuade them to call off the march. But those who met with Kennedy, including Randolph and King, insisted on going forward. “There will be a march,” Randolph bluntly informed the president.

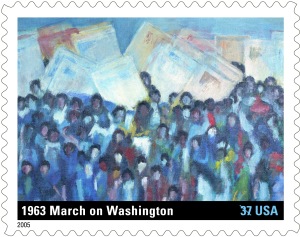

Honor a significant anniversary in the struggle for African-American civil rights, with this collectible, framed print. Click the image for details.

The goals of the march, according to a statement of the organizers, would include a civil rights bill to bring an end to segregated public accommodations; immediate ‘‘desegregation of all public schools’’; voting rights; laws to bar discrimination in employment; a large-scale federal works program ‘‘to train and place unemployed workers’’; and a national minimum wage. Put more broadly, the purpose of the demonstration, King told reporters, was “to arouse the conscience of the nation on the economic plight of the Negro one hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation and to demand strong forthright civil rights legislation.”

Planners initially hoped to get 100,000 participants. But by noon on the day of the march, it became clear the event would attract more than twice that number. All morning long, “freedom trains” arrived in Union Station, at a rate of one every ten minutes. More than 2,000 chartered buses brought demonstrators from all over the country.

The lengths to which some individuals went were truly amazing. One young person skated all the way from Chicago, wearing a sash that read “Freedom,” while an eighty-two-year-old bicycled from Ohio. Twelve youths from Brooklyn walked all the way to Washington, while three teenagers from Gadsden, Alabama, carrying a sign rea ding “To Washington or Bust,” hitchhiked the nearly 700 miles to the nation’s capital. As Bayard Rustin, the main organizer of the event, observed, “It wasn’t the Harry Belafontes and the greats from Hollywood that made the march. What made the march was that black people voted that day with their feet.”

ding “To Washington or Bust,” hitchhiked the nearly 700 miles to the nation’s capital. As Bayard Rustin, the main organizer of the event, observed, “It wasn’t the Harry Belafontes and the greats from Hollywood that made the march. What made the march was that black people voted that day with their feet.”

The violence that the FBI and much of official Washington girded for that day never materialized. A congressman from South Carolina warned that the march was “reminiscent of the Mussolini Fascist blackshirt march on Rome” and of “Socialist Hitler’s government-sponsored rallies in Nuremberg.” But such fears proved unfounded, and the prediction of comedian and activist Dick Gregory that the event would be like “a great big Sunday school picnic” proved closer to the mark.

Marchers heard performances by popular artists of the day. Joan Baez entertained the early-arriving crowd at the Washington Monument by singing “Oh Freedom,” a spiritual made popular by Odetta (the “Queen of American folk music,” in King’s words). Odetta herself followed with the song “I’m On My Way.” Peter, Paul, and Mary performed their new hit, Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and Dylan sang a ballad about the recent murder of civil rights leader Medgar Evers.

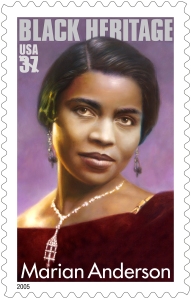

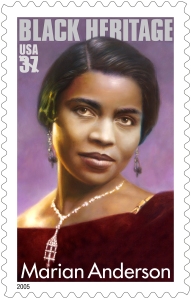

Later in the program, as the crowd gathered before the Lincoln Memorial, Marian Anderson, famous for her historic concert at the memorial in 1939 (after being denied the use of Constitution Hall due to her race), sang “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” Mahalia Jackson also stirred the crowd with “I Been ‘Buked and I Been Scorned,” a spiritual with roots in the slave experience.

Later in the program, as the crowd gathered before the Lincoln Memorial, Marian Anderson, famous for her historic concert at the memorial in 1939 (after being denied the use of Constitution Hall due to her race), sang “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” Mahalia Jackson also stirred the crowd with “I Been ‘Buked and I Been Scorned,” a spiritual with roots in the slave experience.

Various speakers addressed the crowd, but one in particular besides King stood out. John Lewis, representing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, delivered a fiery speech that, even after being toned down at the insistence of the Catholic Archbishop of Washington, D.C., still burned with passion. To those who counseled patience, Lewis responded, “We do not want our freedom gradually but we want to be free now. We are tired. We are tired of being beat on by policemen. We are tired of seeing our people locked up in jail over and over again, and then you holler ‘Be patient!’ How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now!”

When King stepped to the podium, Randolph introduced him as “the moral leader of our nation.” King began by noting the momentous nature of the occasion, calling it “the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.” He then spoke from the text he had prepared the night before. Asserting that the promises of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Emancipation Proclamation remained unfulfilled for black citizens, he compared those promises to a “bad check” that the marchers had come to cash to obtain “the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

When King stepped to the podium, Randolph introduced him as “the moral leader of our nation.” King began by noting the momentous nature of the occasion, calling it “the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.” He then spoke from the text he had prepared the night before. Asserting that the promises of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Emancipation Proclamation remained unfulfilled for black citizens, he compared those promises to a “bad check” that the marchers had come to cash to obtain “the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

King continued reading from his text until he quoted the prophet Amos: “We will not be satisfied until ‘justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.’” The crowd roared in response, and King skipped whole paragraphs of his prepared speech and asked the marchers to “go back” to Mississippi, to Alabama, and to the “slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.” Behind him, Mahalia Jackson, who had heard King speak before about his dream of a renewed America, shouted, “Tell them about the dream, Martin!” As King later explained: “All of a sudden, this thing came to me that I have used—I’d used it many times before, that thing about ‘I have a dream’—and I just felt that I wanted to use it here.”

Wear your support on your sleeve and commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and The 1963 March on Washington Forever® stamp with this collectible t-shirt. Click the image for details.

And from that point on King delivered the heart of his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. He offered a powerful and prophetic vision of an America freed from racism, unlike anything in the political discourse of the 1960s. As historian Drew Hansen writes, King “added something completely fresh to the way that Americans thought about race and civil rights. He gave the nation a vision of what it could look like if all things were made new.”

The march itself was just as important as King’s speech. Philip Randolph called it “the most beautiful and glorious day” of his life. King’s lieutenant, Ralph Abernathy, similarly called the march “the greatest day in my life.” The huge turnout, he believed, demonstrated “unity in the black co mmunity for the cause of freedom of justice.” Bayard Rustin told the southern poet Robert Penn Warren that the march gave African Americans “an identity which is a part of the national struggle in this country for the extension of democracy.”

mmunity for the cause of freedom of justice.” Bayard Rustin told the southern poet Robert Penn Warren that the march gave African Americans “an identity which is a part of the national struggle in this country for the extension of democracy.”

Less than a year after the march, Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which desegregated public institutions and outlawed job discrimination. Soon thereafter the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which provided for federal oversight of voting rights in the South, became the law of the land.

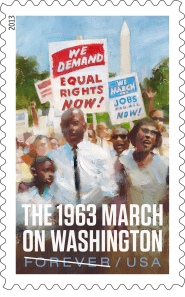

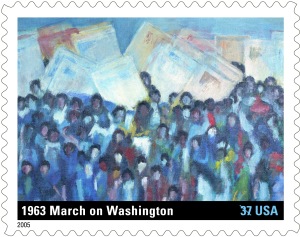

The 1963 March on Washington stamp is being issued as a Forever® stamp. Forever stamps are always equal in value to the current First-Class Mail® one-ounce rate.

The 1963 March on Washington stamp is being issued as a Forever® stamp. Forever stamps are always equal in value to the current First-Class Mail® one-ounce rate.

The 1963 March on Washington stamp showcases the National Mall in Washington, D.C. On National Public Lands Day, volunteers will rake leaves, pick up litter, and beautify the area.

The 1963 March on Washington stamp showcases the National Mall in Washington, D.C. On National Public Lands Day, volunteers will rake leaves, pick up litter, and beautify the area.