Four bull’s-eye postmarks and one standard four-bar cancellation are applied in four quadrants to strike all 12 stamps in this Modern Art in America 1913-1931 cancelled stamp sheet. Click the image for details.

The , issued 100 years after the Armory Show opened in New York, truly capture the spirit of that groundbreaking event. The Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, New Jersey, just wrapped up an exhibition called “The New Spirit: American Art in the Armory Show, 1913.” We recently caught up with Gail Stavitsky, the museum’s chief curator, who graciously answered some of our questions. Here’s a slightly condensed version of our conversation:

Why was the Armory Show so significant?

The original Armory Show was really a landmark exhibition because it was the first large-scale exhibition of modern art in America. It really introduced major artists like Matisse, Picasso . . . and others on a large scale to American audiences. Because before then, you really could’ve only seen a few shows in a very small gallery run in New York City by Alfred Stieglitz on a fourth floor walk-up at 291 Fifth Avenue. There just wasn’t much that you could see, and so [the Armory Show] was the first opportunity to see modern art on a large scale. And of course not only European art, but American art as well, which comprised of two-thirds of the show.

And the other really major importance is that the whole modern art market opened up as a result of the Armory Show. It was after that time that major collections were formed and there was a whole new group of galleries that were founded after the Armory Show. And ultimately, for example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, when it was founded in 1929, it was really an outgrowth of the Armory Show.

What was your goal in developing the “New Spirit” exhibition?

We felt that the best way to celebrate the centennial of this really important event was to try to look at it in a new way, and to focus on the American art. That is very much the mission of the Montclair Art Museum, to engage in new scholarship and new points of view about American art. And we were aware of the fact that American art actually comprised two-thirds of the works of art on view, of which was over 1,200 works. And the show was organized by American artists, and yet the emphasis is so much on European  art. Not only Matisse and Picasso, but also Marcel Duchamp—[his] painting, the Nude Descending a Staircase, was considered the big scandal at the Armory Show. And so that’s what people kind of think about when they think about the Armory Show. They don’t really think about Edward Hopper and Robert Henri and Stuart Davis and the many American artists, some who are well-known today, and a lot who are unfortunately forgotten and who deserve to be better-known. So we really wanted to also revive the reputation of artists like E. Ambrose Webster from Boston, who most people have never heard of before, and say, “here’s a really important progressive artist at the time and deserves our attention now.”

art. Not only Matisse and Picasso, but also Marcel Duchamp—[his] painting, the Nude Descending a Staircase, was considered the big scandal at the Armory Show. And so that’s what people kind of think about when they think about the Armory Show. They don’t really think about Edward Hopper and Robert Henri and Stuart Davis and the many American artists, some who are well-known today, and a lot who are unfortunately forgotten and who deserve to be better-known. So we really wanted to also revive the reputation of artists like E. Ambrose Webster from Boston, who most people have never heard of before, and say, “here’s a really important progressive artist at the time and deserves our attention now.”

How did you go about finding some of the primary documents associated with the Armory Show (letters, floor plans, sales records)?

We were very fortunate to have an important collaborator in the Archives of American Art, which is part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. And they’re really the major repository for any papers that pertain to the Armory Show. They’re the ones with the key documents and the original records, a lot of which are part of the papers of an artist named Walt Kuhn. And there are also papers from another organizer Walter Pach. They have a variety of papers and records there. And so what we did, we worked with them. They have an entire gallery in the show that is devoted to these precious records that they lent to our museum. So I really want to emphasize the importance of their role.

What’s your favorite aspect of the exhibit?

I particularly enjoy the way that we were able to install and present the works, because we wanted to recreate, give kind of a feeling of how the original show was installed. So, we purchased artificial greenery to try to give a sense of the original swags of greenery that were part of the interior decoration of the Armory Show.

And it was a lot of fun being able to present works by both well-known artists and lesser-known Americans in that context and to present such a variety of work, because the work really ranges from realism and impressionism to abstract art by a not-very-well-known artist named Manierre Dawson, who was one of the first abstract artists in the world. [He was] an artist who lived in Chicago and who had his work on view at the Art Institute of Chicago, which was the second stop on the tour of the Armory Show.

The European artists featured at the Armory Show tend to be associated with it, but there were lots of great American works there, too. Why do you think the American artists involved weren’t treated with as much reverence?

I think the reason really has to do with what I guess I would call myth and misconception about the Armory Show that were perpetuated, interestingly enough, by some of the artists themselves initially. And then, especially by the succeeding generation of critics and art historians, which have kind of tended to say the American art is boring and provincial in comparison to the European art, which is more avant-garde. . . .

There was kind of this myth that the Americans didn’t much attention in the newspapers, and that the American artists felt inferior, and felt that their work wasn’t as exciting. Some of that was because artists like Jerome Meyers, who wrote a book in the 1940s saying that European artists really stole our thunder. So I think some of those attitudes were kind of picked up by other critics and writers and historians in later years and so what we did is we really went back to the original newspaper clippings and reviews. And you know what? Actually, quite a bit of attention was paid to American art. And a lot of it was very positive at the time of the show. I guess somehow it’s been forgotten. That was another part of our mission, to talk about the critical reception and how American artists were seen as progressive.

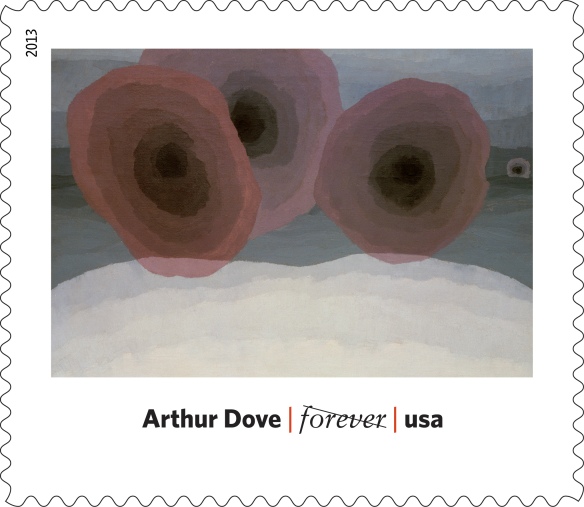

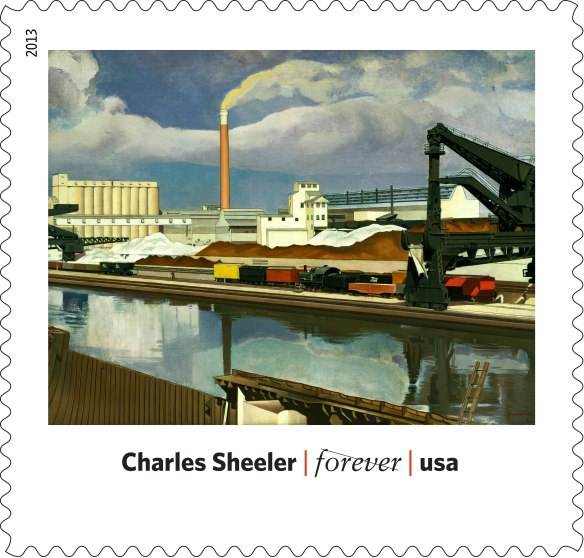

The was released on March 7, 2013. It is currently available online, by calling (), and in Post Offices nationwide.