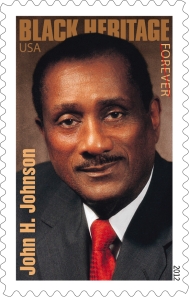

The 35th stamp in the Black Heritage series was released today and it honors John H. Johnson, the trailblazing publisher of Ebony, Jet, and other magazines, and an entrepreneur who in 1982 became the first African American listed by Forbes magazine as one of the 400 wealthiest people in America. Johnson overcame poverty and racism to build a business empire embracing magazines, radio stations, cosmetics, and more. His magazines portrayed black people positively at a time when such representation was rare, and played an important role in the civil rights movement.

The 35th stamp in the Black Heritage series was released today and it honors John H. Johnson, the trailblazing publisher of Ebony, Jet, and other magazines, and an entrepreneur who in 1982 became the first African American listed by Forbes magazine as one of the 400 wealthiest people in America. Johnson overcame poverty and racism to build a business empire embracing magazines, radio stations, cosmetics, and more. His magazines portrayed black people positively at a time when such representation was rare, and played an important role in the civil rights movement.

Johnson was born in humble circumstances on January 19, 1918, in Arkansas City, Arkansas, a Mississippi River town. His father, Leroy Johnson, was killed in a sawmill accident; subsequently, in the Great Flood of 1927, the three-room, tin-roofed house he lived in with his mother, Gertrude (later Williams), floated away. They recovered with help from the Red Cross.

At that time, educational options were limited for black students in Arkansas City. The schools were segregated and there were no black high schools. Johnson’s mother saved money to be able to move to Chicago in search of greater educational opportunities for her son, who was a good student. They migrated north in 1933.

Cultural Diary Page

At DuSable High School, despite being teased for his country ways, Johnson quickly distinguished himself. He was editor of the school paper and president of his class, graduating in 1936. He won a tuition scholarship to the University of Chicago, but could not afford to attend. He explained his circumstance to Harry Pace, a successful black businessman, who offered Johnson a part-time job as an office boy at his insurance company and suggested he attend school part-time.

Working in a black-owned business allowed Johnson to see how he might some day own a company of his own. One of his duties was to compile a digest of articles to keep Pace informed about black American life. This gave Johnson the idea to start his first magazine, loosely patterned after the popular Reader’s Digest. In 1942, using his mother’s furniture as collateral on a $500 loan, he launched Negro Digest, which became an instant success. Its circulation doubled almost overnight after Johnson persuaded First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to write an article on the topic, “If I Were a Negro,” published in October of 1943.

The popularity of Negro Digest inspired Johnson to found another magazine, Ebony, three years later. It, too, was an immediate success, selling 25,000 copies in its first issue, and rapidly became Johnson’s flagship publication. Its circulation eventually rose into the millions.

A monthly general-interest magazine, Ebony was similar to the popular Life and Look. When it was launched in 1945, there were no black players on major league baseball teams, and black representation in the mainstream media, when it could be found, was often negative. In its articles about current events and cultural issues, Ebony highlighted African-American success stories. For its 40th anniversary issue in 1985, Jo hnson spoke of his magazine’s strategy: “We try to seek out good things, even when everything seems bad. … We look for breakthroughs, we look for people who have made it, who have succeeded against the odds, who have proven somehow that long shots do come in.” He could have been describing himself.

hnson spoke of his magazine’s strategy: “We try to seek out good things, even when everything seems bad. … We look for breakthroughs, we look for people who have made it, who have succeeded against the odds, who have proven somehow that long shots do come in.” He could have been describing himself.

The recognition that African Americans were hungry for positive images of black life was critical to Johnson’s success. “I thought my way out of poverty. Ebony was my passport,” he once remarked. In 1946, the year after it was started, Ebony landed its first national advertising account (with Zenith). Selling advertising space to white-owned corporations and persuading them to use black models in their ads were major breakthroughs.

In addition to these successes, Ebony played an important role in the civil rights movement. Johnson was a friend and supporter of Martin Luther King, Jr., and provided important coverage of protest marches and other events. Even during tension-filled times in the Deep South, photographers from Ebony—white or black, depending on the circumstances—were on the scene to capture the news. Johnson’s magazines are an invaluable resource for students of American history. In 1985, he said, “I hope future historians will say that we changed the negative image Black people had of themselves.”

Six years after launching Ebony, in 1951, Johnson launched the newsweekly Jet. Other magazines followed, and Johnson’s business empire grew as he began publishing books, producing for television, and buying radio stations. In 1973, he created Fashion Fair Cosmetics, a line of beauty products. He also acquired control of the Supreme Life Insurance Company, where he had started out as an office boy.

Six years after launching Ebony, in 1951, Johnson launched the newsweekly Jet. Other magazines followed, and Johnson’s business empire grew as he began publishing books, producing for television, and buying radio stations. In 1973, he created Fashion Fair Cosmetics, a line of beauty products. He also acquired control of the Supreme Life Insurance Company, where he had started out as an office boy.

As Johnson’s influence, accomplishments, and fortune grew, he received many prizes and honors. He joined Vice President Richard Nixon on a goodwill tour of Africa and served as a Special United States Ambassador for Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) awarded him its prestigious Spingarn Medal in 1966. Six years later, in 1972, his industry peers named him publisher of the year—a prize Johnson compared to winning an Oscar. In presenting Johnson with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1996, President Bill Clinton lauded him for giving hope to African Americans during difficult times. A panel of experts polled by Baylor University in 2003 named Johnson “the greatest minority entrepreneur in American history.” That same year, Howard University named its journalism school after him.

From poverty to the pinnacle of American society, Johnson’s journey was extraordinary. In 1989, he published his autobiography, Succeeding Against the Odds, in which he credited his mother with much of his success. She taught him that he couldn’t succeed without hard work, but also that some people work hard and fail; he recognized that he was lucky. In the concluding section of his autobiography, he wrote, “And if it could happen to a Black boy from Arkansas City, it could happen to anyone.”

Johnson died August 8, 2005, of congestive heart failure. His daughter, Linda Johnson Rice, is CEO of Johnson Publishing Company.

The Black Heritage stamp honoring John H. Johnson is being issued as a Forever® stamp. Forever stamps are always equal in value to the current First-Class Mail one-ounce rate. In addition to the panes of stamps and Cultural Diary Page (see above), collectors will also be interested in the , , , , and .

I got mine last week and will get more